Long Tone: Thesis Studio with David Gersten / Cory Bertelsen

The Breath Inside the Fire

Cory Bertelsen

The studio, at its best, is not a room but a terrain, a site of exploration, excavation, and slow discovery. It is the place where we learn to inhabit our questions, to live inside our curiosities long enough for them to reveal their internal logic. When we enter the studio in this way, not as a stage for performing works but as a field for inquiry, something subtle and transformative becomes possible. The work stops being something we show and becomes an enactment of uncovering, of listening, of searching.

For Cory Bertelsen, the Long Tone Studio became exactly this kind of field. But before he could enter it fully, he had to clear away the noise, the expectations of the art world, the pressure to produce, the inherited assumptions about what counts as art. This clearing is its own form of excavation. It requires a quieting of the self, a tuning of the ear, a willingness to hear the small, true curiosities that live beneath the louder demands of culture. These curiosities are often fragile. They do not insist. They wait.

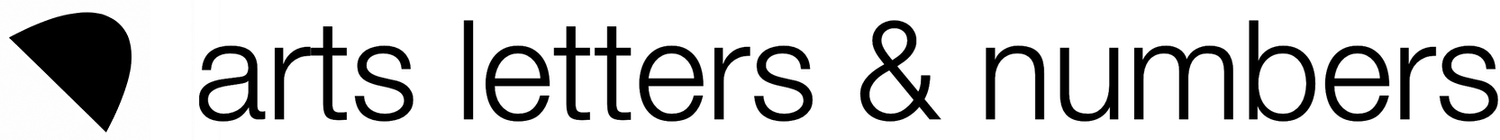

Cory’s curiosity was simple, elemental: he wanted to understand how a combustion engine works. He found an old motorcycle engine and felt, at first, the familiar pressure to transform it into art, to make something artful out of it. But beneath that impulse was something deeper, the raw, almost childlike recognition that he did not know how an engine actually works. And that not-knowing carried a charge. It felt alive, honest, unguarded.

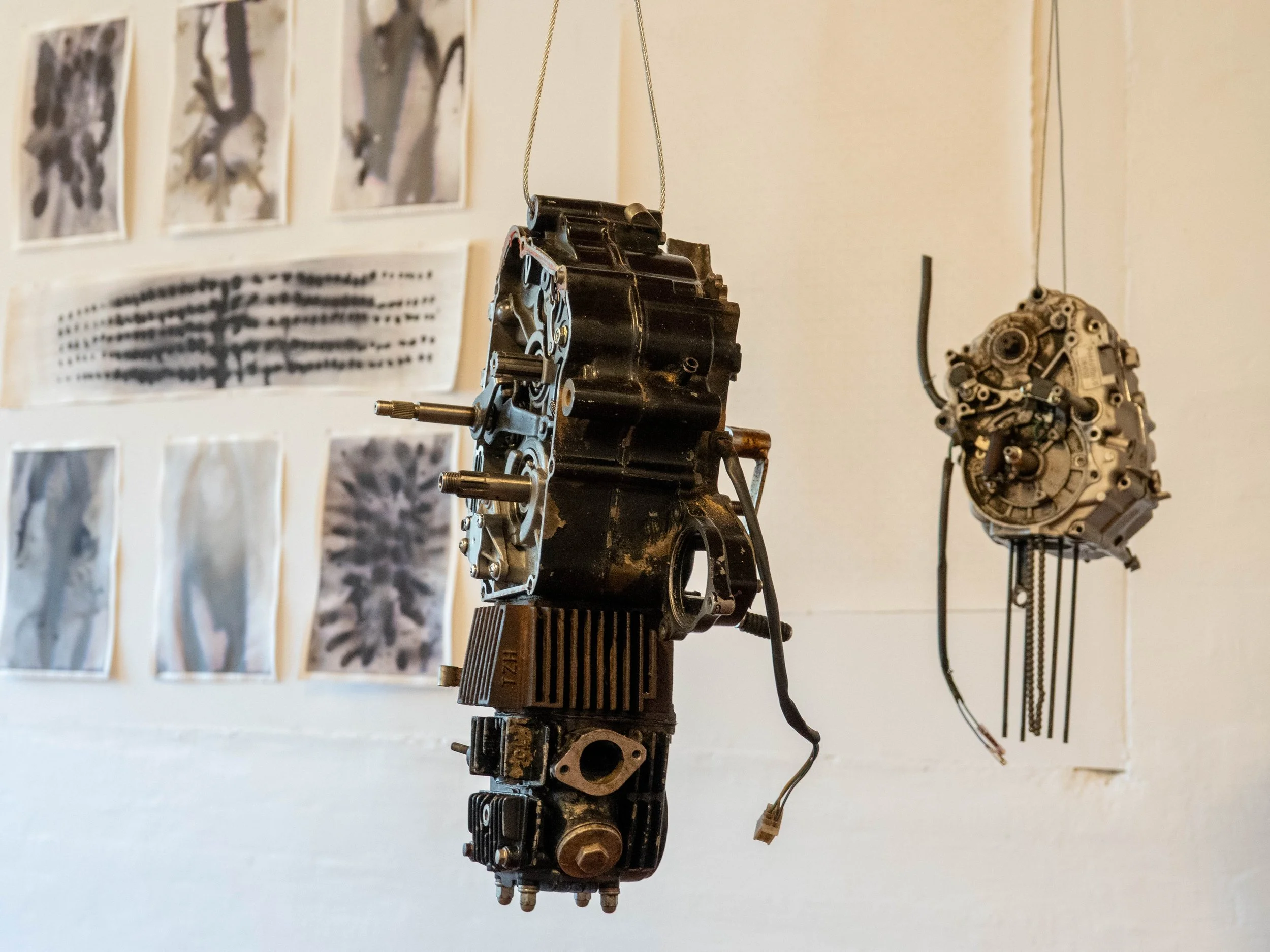

We agreed that the act of learning, of truly learning something unknown, could itself be the art. The art of listening. The art of paying attention. The art of following a question all the way into its interior. If he removed every precondition of what art is supposed to be and simply tried to understand the engine on its own terms, that would be a journey worth taking. To take it apart. To understand its workings. To discover its internal logic. To put it back together. In essence, to let the engine teach him.

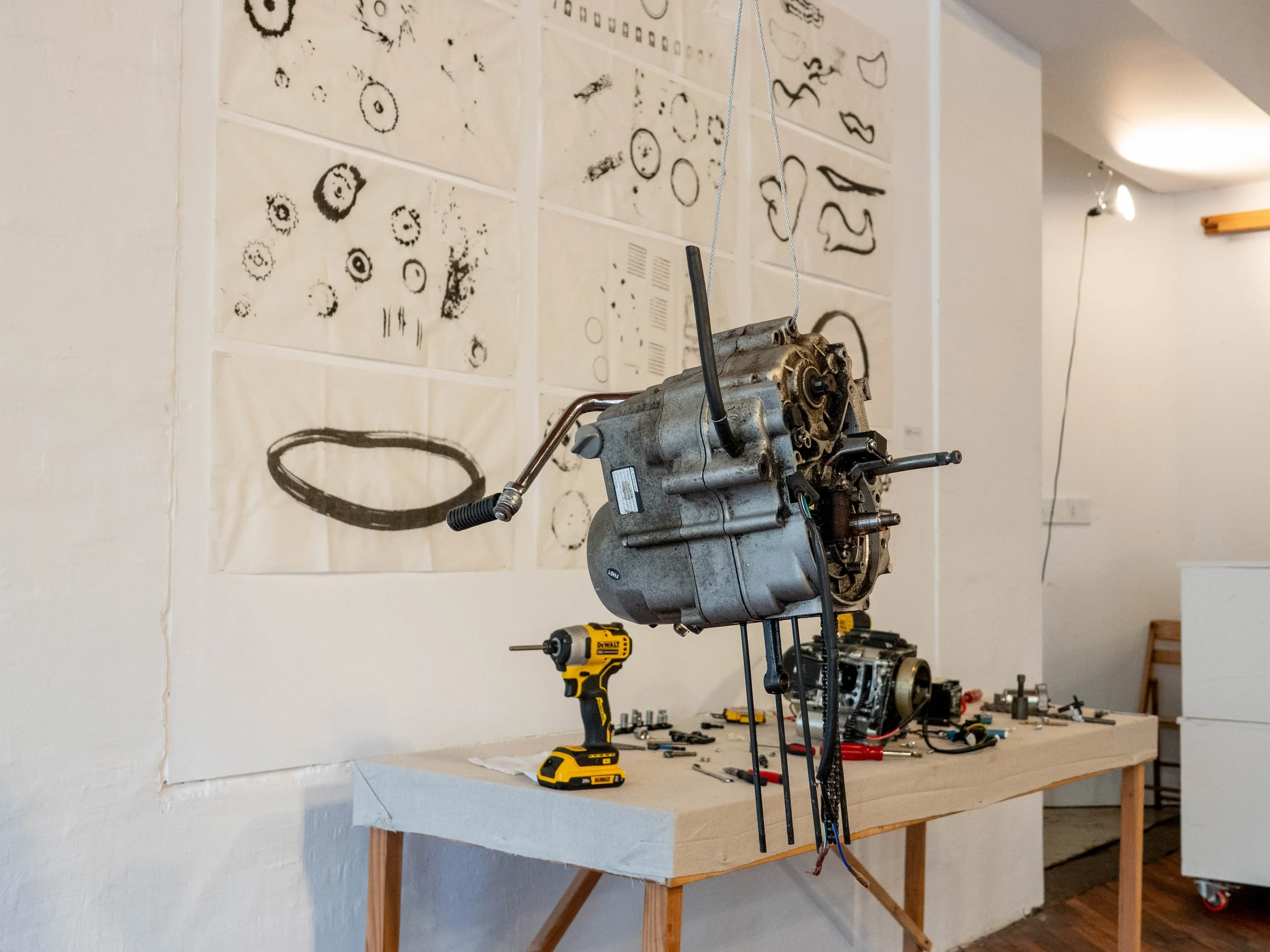

This journey was not only about Cory and the engine, but also about the people who imagined the engine in the first place, the machinists, mechanics, engineers, and dreamers who understood that metal could be shaped into a choreography of breath and fire. It was about understanding their grammar, listening to their voices as they speak through the spaces and structures of the engine. A combustion engine is precisely machined steel, yes, but it is also a dance. Someone had to imagine the delicate timing of valves, the mixing of vapor and air, the compression and release, the spark that ignites the whole sequence. Someone had to understand the environment these interactions required, the tolerances, the pressures, the rhythms. This understanding emerges within the culture of craft: a culture of listening, of attending to nuance, of shaping the world with both force and tenderness.

To understand this, consider the welding torch, also called a blow torch. From the outside, it appears ferocious: a 4000-degree flame, loud, bright, intimidating. But inside this ferocity is an astonishing fragility. Yes, the heat melts solid steel into liquid metal, but heat alone does not make a weld. What makes the weld is the breath of the torch — the gentle stream of air that blows the liquid metal down the line. This breath is barely stronger than our own. Move too quickly and the liquid metal is left behind; too slowly and the flame melts a hole straight through. Inside the roar of the flame is a gesture of extraordinary delicacy. The weld is made not by force, but by breath.

The combustion engine contains the same paradox. At its core, an engine is a choreography of air and liquid. The carburetor mixes gasoline with air into a fine vapor. This vapor is drawn into the cylinder as the intake valve opens, then sealed inside. The piston rises, compressing the mixture until the spark plug ignites it, a tiny explosion that drives the piston back down. Then the exhaust valve opens, releasing the burnt gases. This cycle repeats thousands of times per minute, perfectly timed by the camshaft and timing chain, a mechanical rhythm so precise it borders on the miraculous.

Inside the ferocity of combustion is the same fragile breath, the movement of air, vapor, valves, timing, the delicate balance that makes the whole system possible. What seems hard, loud, mechanical, even violent contains at its center a choreography of astonishing subtlety.

This understanding, that what appears frightening from the outside often contains the most fragile stories, is also the nature of the creative process. To follow a curiosity into the unknown requires both strength and vulnerability. It requires the courage to dismantle something, the patience to understand its internal logic, and the humility to let the material, whether steel, air, fire, or a question of one’s path, speak back. It requires the willingness to be changed by what we encounter.

Cory’s work in the Long Tone Studio was about engines, yes, but more deeply, it was about transforming his understanding of what it means to learn, to listen, to follow a question. It was about discovering that inside every ferocity is a breath, inside every material is an imagination, inside every question is a path. And when we inhabit our questions fully, when we let the studio become a living, breathing field of inquiry, we discover that the work is not something we make to display our ideas, but the experience of uncovering our curiosities, of learning to listen to them, and consequently, to the world.

David Gersten | December 2025

Founding Director

Arts Letters and Numbers