Long Tone: Thesis Studio with David Gersten / Paria Shahverdi

A New Dawn in the Studio

Paria Shahverdi’s Living Still Life

Walter Benjamin, gazing at Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, imagined the angel of history: its face turned toward the wreckage of the past, wings caught in a storm that blows it helplessly into the future. This storm, he wrote, is what we call progress. Ahmad Shamloo, in his magnificent poem, Paria, sings of angels who hover between suns and stars, between laughter and lament, guardians of vision who refract desire into multiplicity. To place Benjamin’s backward-blown angel beside Shamloo’s radiant constellation is to glimpse history and poetry entwined: one dragged through catastrophe, the other shimmering with plural voices, each revealing a different temporality of being.

“Paria” is a word born of poetry, literally “plural angels” a name Shamloo created as if summoning a small chorus of guardians into being. He offered this name to his friend’s newborn daughter, Paria Shahverdi, as both a name and a promise. The name carries the sense of many presences, many watchful forces, a constellation rather than a single star. Shahverdi’s installation inhabits precisely this tension. Her woven threads are caught in the storm of perception, binding viewers into a fabric where every gesture becomes both debris and dawn. Like Foucault’s reading of Las Meninas, the work stages a drama of gazes, refracting vision through multiple positions, folding the viewer into its shifting center. And, echoing Merleau-Ponty’s insistence that “the body sees and is seen,” Shahverdi collapses subject and object—angel and angle—into a lived field of relation. The angel of history, the angel of poetry, and the angel of perception converge here, not as metaphors alone, but as presences woven into the very atmosphere of her studio.

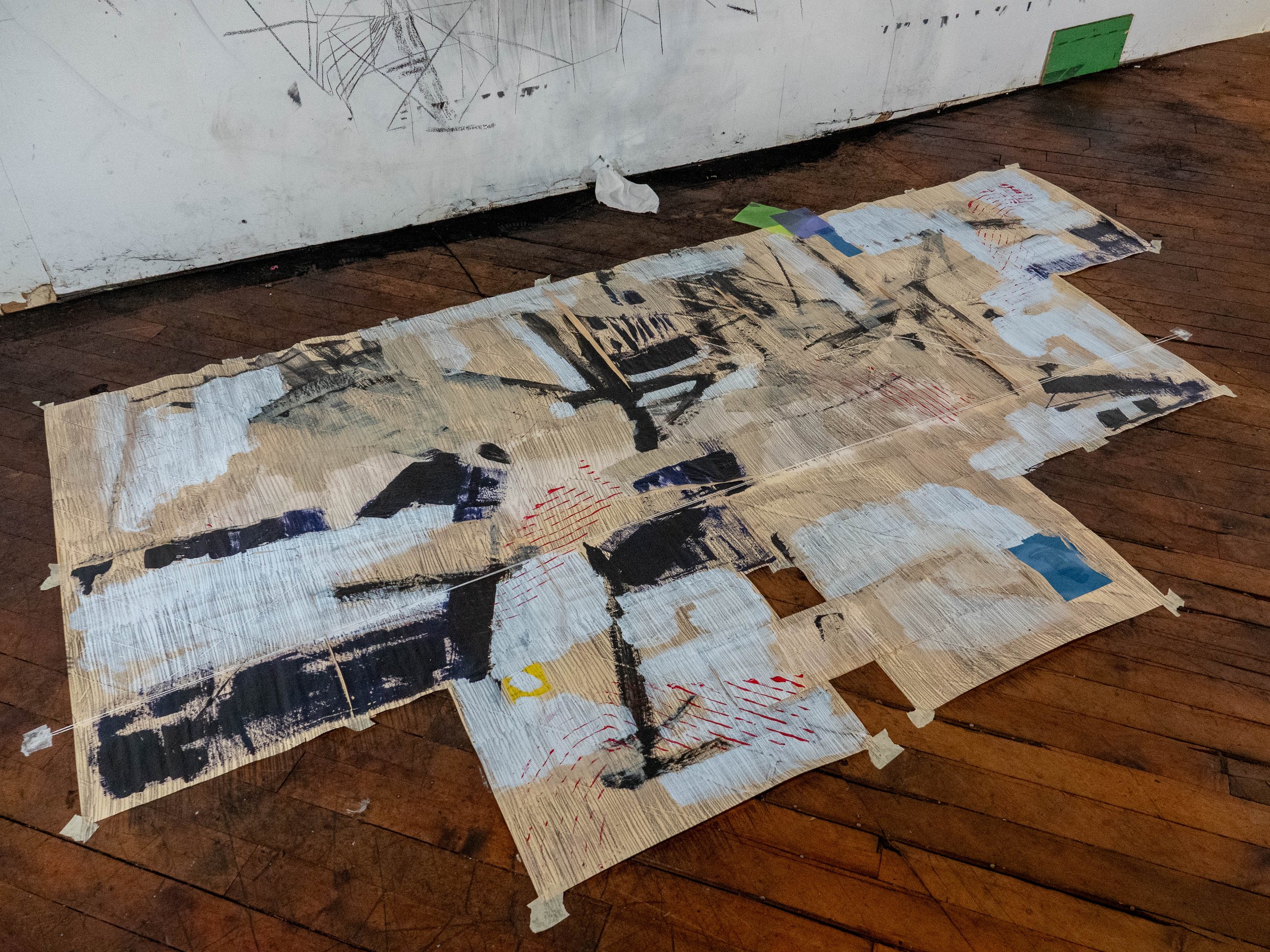

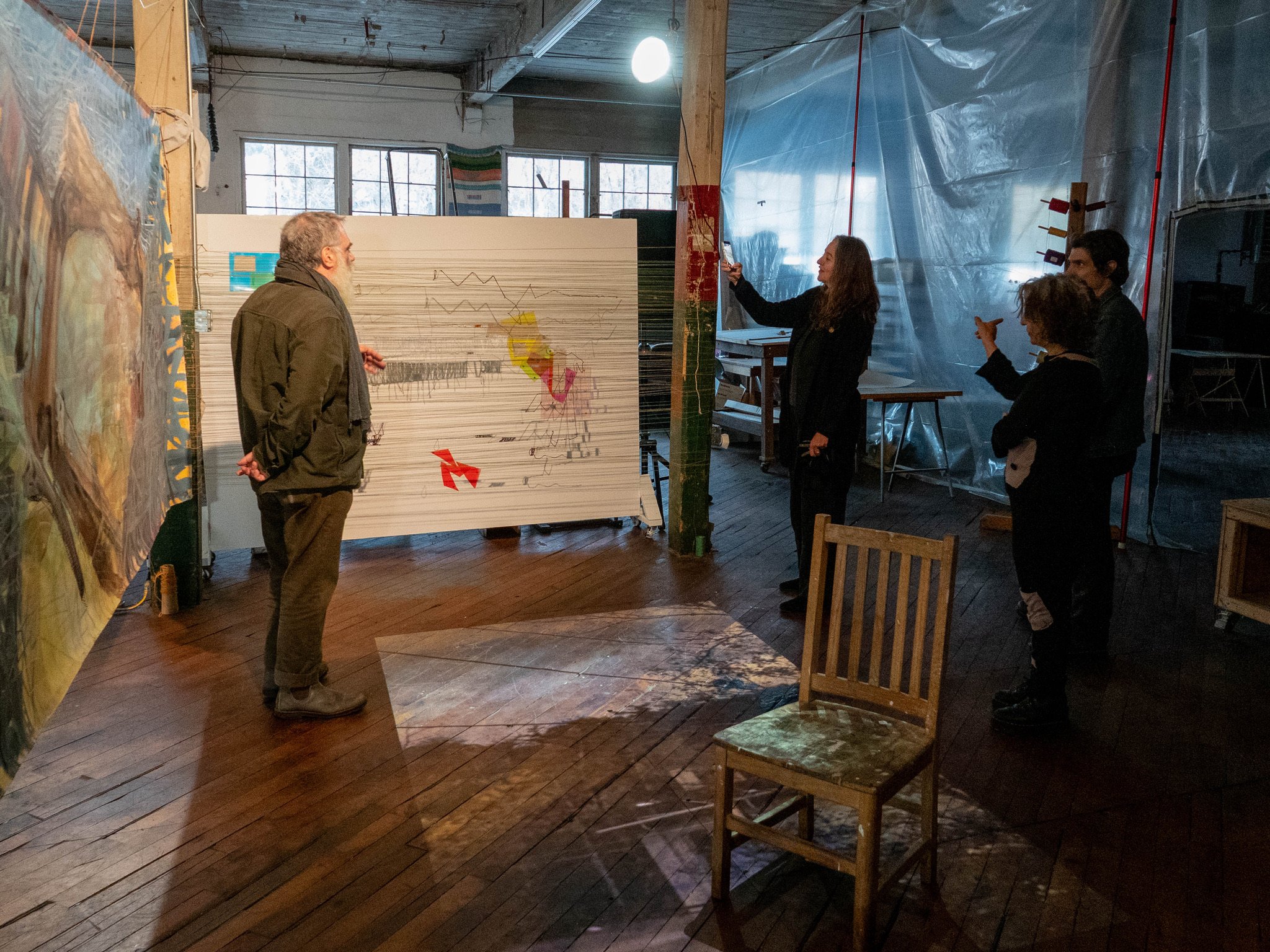

Created in the Long Tone Studio at Arts Letters & Numbers, the work resists categorization. It is painting, drawing, weaving, sculpture, film, and performance all at once, but more deeply, it is a reconstitution of the conditions of seeing. By stringing yarn between columns, Shahverdi thickens the picture plane into a palpable surface, turning drawing into environment. The threads shimmer like a holographic membrane, refracting light and gaze into multiple dimensions. What appears as line becomes surface; what appears as surface becomes space. The studio becomes a still life, not a tableau of objects, but a relational atmospheric field where every chair, every thread, every gesture participates in the act of vision. It is a still life that inhabits life, and the life that inhabits the still life.

The chairs intensify this relationality. One stands in the center as subject, another holds a pad of paper, and a third is reserved for the artist, who draws the first chair into the surface of paper held by the second. This triangulation echoes Foucault’s insistence that representation is always refracted through multiple positions. The chairs are angles of vision, but also angels of presence, guardians of perception hovering between silence and revelation. They recall Shamloo’s angels, plural and luminous, but also Benjamin’s angel, caught between wreckage and storm, unable to turn away from history yet compelled into the future. Each chair becomes a station point in a choreography of seeing, a hinge between presence and absence.

Merleau-Ponty’s Eye and Mind deepens this understanding. Painting, he writes, is not a detached representation but a participation in the flesh of the world. Shahverdi’s threads embody this: they are not marks on a canvas but gestures extended into space, vibrating with the body’s movement.

Her three-hour wall drawing wild, exuberant, savage, unrestrained, is less an image than an event, a burst of being that saturates the studio with energy. Each mark is a wingbeat in Benjamin’s storm, both a trace of what has passed and a propulsion into what is yet to come. The drawing’s immediacy is not chaos but immersion, a lived moment of vision that refuses to be tamed.

Henri Bergson’s notion of duration offers another lens. Time, for Bergson, is not a sequence of instants but a continuous flow where each moment carries the memory of the last. Shahverdi’s installation is precisely such a duration. The woven threads accumulate gestures; the chairs accumulate gazes; the drawing accumulates energy; and the film of sunrise projected from the ceiling crowns this temporal unfolding. The dawn is not a static image but a lived experience of becoming, a temporal organism gathering memory even as it unfolds into the future. Benjamin’s angel, blown forward yet facing backward, is mirrored here: the installation gathers fragments of dawn, even as it opens new horizons.

Shahverdi’s work resonates deeply with Shamloo’s poetry, echoing the multiplicities of voice and becoming. Each line is a mark, each mark a sun, each sun a star in a constellation of dawns; each thread an angle of vision, an angel of presence. Together they gather into a heartbeat, a living still life, a poem, a song, a quiet choreography of positions, proximities, and intensities.

The woven threads themselves sing Shamloo’s freedom: dissolving the wall, thickening the picture plane into an openness where light and shadows weave catastrophe into possibility. From this trembling surface, relation gathers, not as ornament, but as a lived insistence that nothing stands alone. Every strand carries the memory of another hand, another rupture, another vow to keep the world from narrowing.

In that density, the work refuses despair; it leans instead toward a future smuggled inside the present, a quiet uprising of form against forgetting, of life against emptiness. Their holographic shimmer reminds us that experience is never flat but layered, refracted, doubled, multidimensional, a living field in which the still life inhabits life, and life, in turn, inhabits the still life.

Through all their lines, layers, marks, light, and shadows, this work announces a new dawn, a gate at the edge of a great lake, a threshold where ancient basement bookshelves become threads, threads become shadow marks, marks become voices, voices become poems, poems become spaces, spaces become life. A child is born, rising through the wreckage and storms, becoming new angels, becoming پریا.

David Gersten | December 2025

Founding Director,

Arts Letters and Numbers