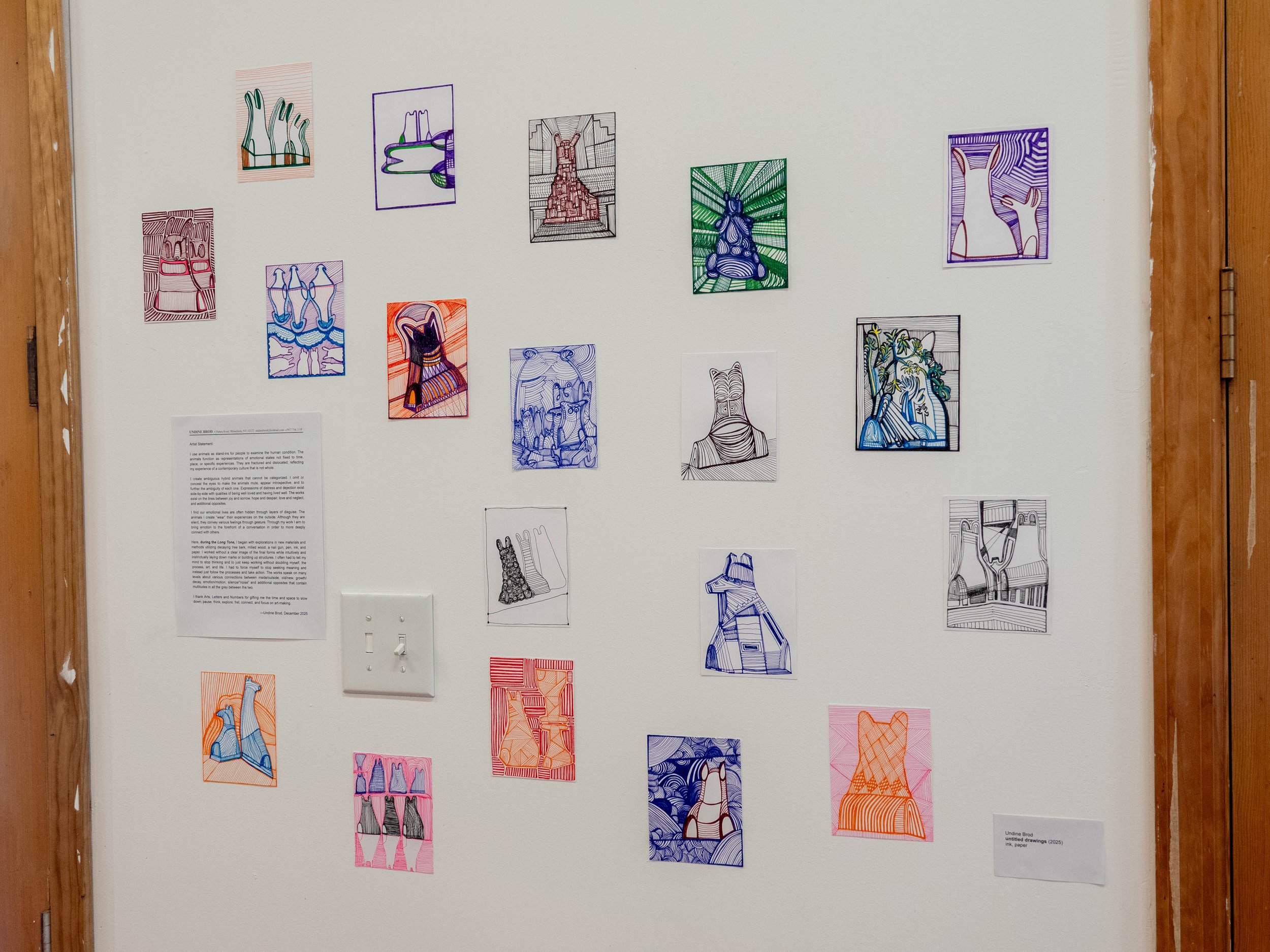

Long Tone: Thesis Studio with David Gersten / Undine Brod

Undine Brod: Bark, Bear, Becoming

Undine Brod’s sculptures emerged from the most direct, physical acts of making: gathering fallen branches, strips of bark, irregular chunks of tree; cutting them on the the chop saw; turning them in her hands to find the angle where one piece might meet another. Nothing was sketched in advance, nothing predetermined. The sculptures grew through an improvisational logic, a cut here, a pivot there, a sudden decision to join two unlikely fragments with the sharp punctuation of a nail gun. The creatures arrived through accumulation, through the rhythm of assembling, through the small negotiations between hand, tool, and material.

At first, the bark always faced outward. The creatures wore the tree’s original skin, its protective layer, its roughness, its history. And here the pun becomes irresistible: an animal barking, the bark of a tree, the bark of a creature not yet named. These barkout beings carry this double bark, this double calling. They are rough, alert, halfformed, as if they have just stepped out of the cave walls. These early beings were literally barking, calling out through their surfaces, announcing themselves through the texture of their origins. They stood somewhere between animal and artifact, between found form and authored form, between the forest and the studio.

As the semester unfolded, the creatures began to evolve. Undine started wrapping them in yarn, not once or twice, but hundreds of times, until the yarn became a second skin. The bark was still there, but now it was concealed and revealed simultaneously, softened and amplified. The yarn gave the creatures warmth, tenderness, vulnerability. It was as if language itself, the naming, the fur of words, had begun to grow over them. They became beings with a kind of interiority, a kind of emotional depth created by having a surface.

And then, in the final phase, the creatures turned inside out. The pale, cut, oncehidden material, now faced outward. What had been interior became exterior. What had been surface became core. It was a literal inversion, but also a conceptual one: a recognition, a representation, a reimagining, the again, the return, the turning over that makes something newly visible. At this point, the creatures begin to look back at you. Not because they have eyes, or even a face, but because something in the assembly, the cut bark, the angled join, the improvised limb, crosses a threshold and becomes more than itself.

Remo Guidieri, in his remarkable lecture series Subterranean, spoke of the cave drawings and the equalization of pressures between the darkened spaces of the caves and the darkened spaces of consciousness in early Homo sapiens. He described how, in this double darkness and its converging pressures, drawing “popped out” marks that were marks and also more than themselves. This, he said, is where representation and excess first touched.

Undine’s creatures emerge from a similar pressure zone, a similar subterranean logic, where the material insists on its own language and the maker listens. Remo once suggested that perhaps we did not become Homo sapiens and then begin to draw, perhaps, within the darkened spaces of the caves, drawing itself set the transition in motion. Undine’s creatures feel born of that same threshold. They are not representations of animals; they are emergent lifeforms assembled through improvisation, attention, and the strange intelligence of materials.

Tom Zummer once asked: What if the cave drawings were not made by our ancestors but by bears? The humor and the enigma of that question open a deep seam in Undine’s work. Her creatures hover in that ambiguous zone where the human and the nonhuman coauthor form. They test the boundary where recognition begins. A bear is not a bear because we named it bear. The creature itself does not know this word. It is a living system in a microclimate of our solar system, moving through its own sensory world, unburdened by the linguistic fur we have draped over it. The name “bear” is our invention, our projection, our fabric of recognition.

Undine’s creatures ask whether we can see the unnamed creature and the named creature at the same time, whether we can hold the raw material and the emergent language without collapsing one into the other. And this brings us to the question: If a bear is not a bear, is a chair a chair?

A chair, that is different, a chair was authored, constructed, articulated. It was brought into existence through a notational language cut into wood, measured, joined, stabilized. A chair is inseparable from the conceptual framework that produced it. The word “chair” is not merely a label; it is part of the object’s architecture.

So the question becomes: If a bear is not a bear, is a constructed bear a bear? Could Undine’s creatures, assembled, improvised, authored, be more bear than a bear itself? Undine’s creatures are not animals, not exactly. They are not chairs, though they are constructed. They are something in between, authored yet alive, improvised yet inevitable, named yet unnamable. They remind us that evolution is not only biological; it is artistic, relational, recursive, a long tone held across time. And in their strange, insideout bodies, they ask us to reconsider what we think we know: If a bear is not a bear, what else might be waiting to become?

David Gersten | December 2025

Founding Director

Arts Letters and Numbers