Oppenheimer's Table

March 1st - March 8th, 2015

The Mill, Averill Park , NY , United States

In March 2015 a group of 25 people from all over the world, and representing a wide spectrum of disciplines, convened upon a snow-covered House on the Hill to take part in “Oppenheimer’s Table” - the first in a series of Arts Letters & Numbers workshops examining and expanding upon the nature of 132 doodles generated from the secret joint committee meetings held in 1947 and chaired by Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer.

The doodles, attributed variously to Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi, I.I. Rabi, and other notable actors within the burgeoning cold war became the conceptual and formal foundation for the exploring of the complex history, culture, and possibilities that lay ahead in our contemporary nuclear age. Through sessions History, Physics and Numbers, Veils, Artifice, Risk and Remains, a framework was established and the Table was set for emergent creative actions to occur within the discourse, across disciplines.

Within an environment of debate and group exercises, the participants embodied the condition of mimesis as a strategy for understanding and inhabiting the doodles. Redrawn, reorganized and re-enacted, the artifacts revealed mysterious internal relations and interdependencies. They became the living model for the participants within “Oppenheimer’s Table”, informing everything from long-format improvisational performances to the sharing of food and stories.

Infinite vast white landscapes of flour, drops of ink slowly diffusing into water, scans of skin and the sound of signs made on a chalkboard all intermingled with isotopes, periodic table food labs and late night Butoh screenings.

The Table has been set and the gestures continue.

1942-1946

The Manhattan Project: The building of the Atomic Bomb, Robert Oppenheimer appointed Director.

July 16, 1945

Trinity, The first detonation of a Nuclear Weapon

Aug 6, 1945

Hiroshima, The first detonation of a Nuclear Weapon in war

Aug 9, 1945

Nagasaki, The second, and last detonation of a Nuclear Weapon in war

August 1, 1946

President Harry S. Truman signed the McMahon/Atomic Energy Act establishing a Congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy [JCAE] for government oversight of every aspect of the national atomic energy program except appropriation; a new Atomic Energy Commission [AEC] for civilian management of atomic industry; a General Advisory Committee [GAC] for scientific input to the AEC; and a Military Liaison Committee [MLC] to handle “Defense concerns.” The McMahon / Atomic Energy Act transferred the control of atomic energy from military to civilian hands, effective from January 1, 1947. Robert Oppenheimer appointed Chairman of the General Advisory Committee (GAC).

November 23, 1947

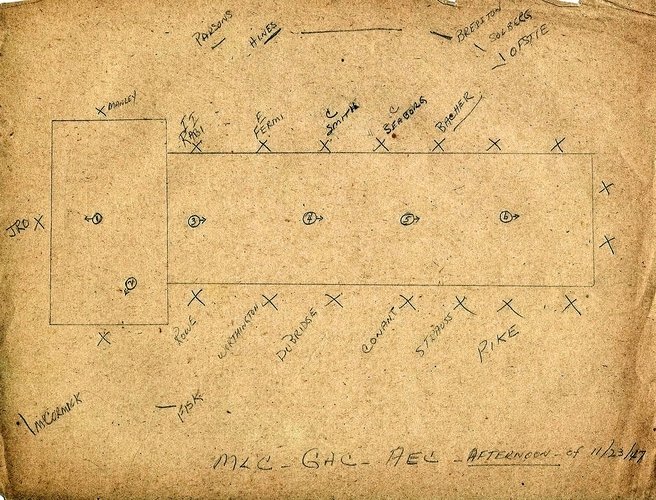

A joint meeting of AEC; GAC; MLC Chaired By Robert Oppenheimer. The Joint Meetings of the AEC; GAC; MLC were highly classified and held under the strictest rules of secrecy. Paper and pencil were provided for doodling, but no notes were taken and nothing was allowed to leave the meeting room. Bryan F. LaPlante was assigned in 1946 as Assistant to the Director of Security for the AEC, at the same time as he was Chief of AEC’s Washington Area Intelligence and Security Office. LaPlante personalized his security job by collecting doodles. He was required to make a ‘clean sweep’ of meeting rooms after the participants had left, and saved all the pieces of paper that bore doodles – annotating them with the date and the name of the artist.

“With its seemingly unlimited growth of material power, mankind finds itself in the situation of a skipper who has his boat built of such a heavy concentration of iron and steel, that the boats compass points constantly at herself and not north. With a boat of that kind no destination can be reached; she will go around in a circle, exposed to the hazards of the winds and the waves” -Werner Heisenberg

A transformative 20th century event, the Manhattan Project, simultaneously produced nuclear weapons and information technologies.

In the immediate aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki the United States Government set in place a legal and committee framework that formed the foundation of the cold war. In 1947, the early joint meetings of this highly secretive committee anchored an evolution of knowledge and power that became the cold war and continues to influence every aspect of our lives today.

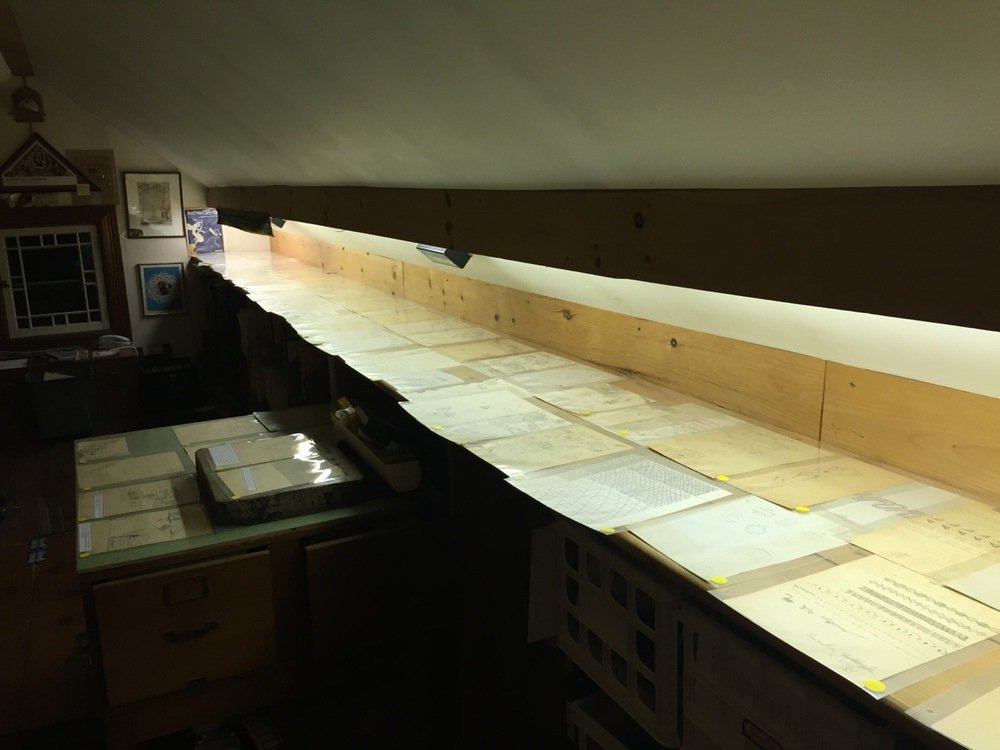

The original doodles collected from the Joint meetings of the AEC, GAC, MLC chaired by Robert Oppenheimer are currently part of the extensive Atomic Archive of Physicist Robert Dalton Harris and writer Diane DeBlois. Numbering well over one hundred examples, these artifacts offer a remarkable ‘capture’ of the moment in time: they contain the questions, peripheral thoughts, imaginations and dreams of the participants of these seminal meetings. In addition to collecting the drawings, Bryan F. LaPlante made a sketch of the table seating arrangement of one of the key meetings, identifying who sat where. This opens remarkable possibilities of reconstructing the geography, of locating the drawings in space and time around Oppenheimer’s table and constructing spatial conversations.

The Manhattan project; The building of the first atomic bomb.

“I have often thought of the odd symmetry of the Sun (in the sky) being an enormous life-giving fusion event, and fragments of the sun on earth (nuclear weapons) being the direct inverse (enormous life-taking fusion events). This vast arc contains a difficult paradox toward imagining the globe’s resources. In principle, we could say that we live in the shadow of Oppenheimer.” -David Gersten

Setting the Table

“Before Hitler invaded Poland in August 1939, theoretical physicists Albert Einstein, Eugene Wigner and Leo Szilard drafted a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt about the advisability of researching the explosive energy of uranium. To achieve both the secret and the bomb, science and government became partners with business. Science provided the knowledge; government provided the power, and it was left to business to produce the goods.

One of the businessman observers on the Joint Chiefs of Staff Evaluation Board, Bradley Dewey, rightly concluded that, unlike all other explosive devices which were tactical weapons, the atom bomb was essentially strategic.

During the War, the need for strict secrecy around the details of the Manhattan Project was a cover for Roosevelt’s decision to make a weapon of mass destruction based on the fear of Hitler. After the War, there was still Stalin.

Until the McMahon Act of 1946, the Government did not really know how to manage the huge industrial complex it had inherited form the atomic bomb project. For almost a year, General Leslie R. Groves had full rein (though Groves was left out of Operation Crossroads). The Act, signed into law 1 August 1946 by President Harry S. Truman, established a Congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy [JCAE] for government oversight of every aspect of the national atomic energy program except appropriation; a new Atomic Energy Commission [AEC] for civilian management of atomic industry; a General Advisory Committee [GAC] for scientific input to the AEC; and a Military Liaison Committee [MLC] to handle ‘Defense concerns.’ Business was AEC; Science was GAC; and Government was both JCAE (Congressional watchdog) and MLC (Military watchdog, connecting to the President as Commander in Chief).

Bryan F. LaPlante was assigned in 1946 as Assistant to the Director of Security for the AEC, at the same time as he was Chief of AEC’s Washington Area Intelligence and Security Office.

LaPlante personalized his security job by collecting doodles. He was required to make a ‘clean sweep’ of meeting rooms after the participants had left, and saved all the pieces of paper that bore doodles – annotating them with the date and the name of the artist. From other papers in his files, it is clear that colleagues knew of this hobby and passed on to LaPlante other doodles they were able to gather.

A joint meeting of 23 November 1947 (AEC; GAC; MLC) introduces people LaPlante had to secure.

The basic table seating was for the GAC: beginning at the upper right of the diagram, near the head of the table and opposite microphone #3 - Isador Isaac Rabi, the 1944 Novel Laureate in Physics and a wartime leader at the MIT Radiation Laboratory and, with Niels Bohr, senior advisors to J. Robert Oppenheimer at Los Alamos (earlier in November he had opposed funding for Ernest Lawrence’s Berkeley lab and its Bevatron in favor of a less expensive accelerator under his wing at the Brookhaven lab); Enrico Fermi, who had won the 1938 Nobel Prize for Physics and had achieved the world’s first self-sustained nuclear reaction in 1942 had gone back to teaching in Chicago after leaving Los Alamos; Cyril Smith, a metallurgist working for the National Defense Research Committee; Glenn Theodore Seaborg, a chemist from Berkeley whose research team had first isolated plutonium. Across the table were: James Bryant Conant, a chemist and president of Harvard; Lee DuBridge, a physicist who had been director of MIT’s Rad Lab; Hood Worthington of du Pont, who had been responsible for building the atomic facility at Hanford; Hartley Rowe, a physicist from Los Alamos who would spark debate over the morality of the Super at later meetings with the comment: ‘We built one Frankenstein.’ At the auxiliary table placed at the head was John Manley acting as secretary and long an assistant of Oppenheimer’s at Los Alamos, and Robert J. Oppenheimer, physicist and former Director at Los Alamos as Chairman.

Seated at the foot of the table were three commissioners from the AEC: Robert Bacher, from CalTech, the only scientist on the commission; Lewis Strauss, a self-made millionaire investment banker, former aide to President Herbert Hoover, and rear admiral in the Bureau of Ordnance during the war; and Sumner Pike who would vote against the hydrogen bomb in subsequent meetings.

Ranged to Oppenheimer’s right (and on the upper left of the plan), away from the table but with a microphone accessible, were the ‘big guns’ of the AEC: General James McCormack who was head of the AEC’s Division of Military Application and the AEC’s recently appointed director of research; and James B. Fisk, the watchdog of government spending who had been against further government funding of national civilian laboratories. Three months before this meeting, a revitalized alliance between the government and the Berkeley lab had been drafted under Ernest Lawrence’s leadership at Bohemian Grove in California. Fisk’s presence embodied a mighty change for science: theoretical research now depended entirely on the ability to negotiate for government contracts.

In the wings on the side of the table to Oppenheimer’s left were ranged the MLC representatives: William “Deacon” Parsons of the U.S. Navy who had been in charge of the design and delivery of the ‘uranium-gun’ bomb, ‘Little Man,’ to Hiroshima; and four other military personnel from the liaison committee.

To consider just four of these men and their doodles from that meeting:

General McCormack doodling the good life of a country estate with tennis courts (in other meetings he doodled golf games and pinup girls), represents the warrior hedonist, boisterous and brutish.

Rabi playing with words like Curie/puerile, synoptic/syncretic, and zeroing in on Biological, is the playful, kabbalistic, scientist.

Sumner Pike, the retired businessman who had made two fortunes in oil investment, signals his metronomic boredom with the whole committee process.

Oppenheimer with his comic/tragic Janus faces doodles ambivalence. This is the only drawing attributed to him in LaPlante’s collection – perhaps he felt himself under the pall of government scrutiny, and of colleagues’ suspicion of his role. In the summer of 1948, when Oppenheimer’s security file (a foot high and weighing some twelve pounds) landed on David Lilienthal’s desk, his response was: ‘Suspicion, suspicion, suspicion. And what an opportunity to gouge a man you don’t like, one who has disagreed with you. Godalmighty!’ Many of the important players of these joint Committee meetings would meet (at least in testimony) at the 1953 hearings which revoked Oppenheimer’s security clearance.

One of the first “special projects” of the AEC that involved security issues was the isotope program, and how to regulate the international distribution of information (the first question was whether they could supply isotopes to Joliot-Curie in France, an avowed Communist). “I believe we should take the strong moral position that isotopes are not useful to increase the military potential of other countries, or jeopardize the security of our own, that we are distributing them for the benefit of mankind, that they can be used in research that will be freely published, and that we do not care who discovers a cure for cancer, a French Communist, an Irish priest, or a Swiss democrat.”

Participants

Emma Faith Hill . Bryan Wilson . Ingrid Koenig . Anca Matyikuv . Jessica Shimazu . Chelsea Limbird . Ruairidh Macleod . Crystal Walters . Christina Rosati . Marc Rochette . Juliana Kusyk . Kristin Runarsdottir . Ana Patete . Diane Deblois . Rob Harris . David Gersten . Ché Perez . Frida Foberg . Rikke Jørgensen . Tine Bernstorff Aagaard . Chris Rose . Zubin Singh . Rebecca Woodmass . Amara Abdal Figueroa . Laura Genes . Loren Howard